From the second chapter of Jonathan Ned Katz’s Love Stories: Sex Between Men Before Homosexuality:

In December 1837 at Yale, Dodd composed or transcribed a revealing, rhymed ditty, “The Disgrace of Hebe & Preferment of Ganymede,” about a dinner for the gods given by Jove, at which the beautiful serving girl, Hebe, tripped over “Mercury’s wand,” exhibiting, as she fell, that part “which by modesty’s laws is prohibited.” Men’s and women’s privates were on Dodd’s mind—eros was now closer to consciousness. Angry at Hebe’s “breach of decorum,” Jove sent her away, and called Ganymede “to serve in her place. / Which station forever he afterward had, / Though to cut Hebe out… was too bad.”

Considering Dodd’s cutting out Julia Beers [his girlfriend] for John Heath, Anthony Halsey, and Jabez Smith [fellow college students for whom he professed love or intense friendship], his poem shows him employing ancient Greek myth, and the iconic, man-loving Ganymede to help him comprehend his own shifting, ambivalent attractions. At Yale, Dodd read the Greek Anthology and other classic texts and began to use his knowledge of ancient affectionate and sexual life to come to terms with his own—a common strategy of this age’s upper-class college-educated white men.

This passage leads to the sort of thesis-related observations I usually try to keep off this blog, but given the relationship of the work Katz does to the questions of close-reading I contemplated yesterday, and the broader implications of his thesis about the historical contextualization of identity categories, it’s worth discussing here. Briefly, Katz has written this book to talk about men who loved and desired other men in America, but before such a thing as homosexuality existed. Through detailed case studies and work with both literary and more traditionally historical sources, he makes a case for a 19th century in which men’s sexual identities and relationships to sexual identity were very different from those of men in our own time. He fights against an essentialist reading of homosexuality across generations, and focuses instead on how 19th-century American men perceived their own relationships with each other, not what modern Americans might read into them. He finds (well, so far; I’m only on Chapter 4) that men often lacked the appropriate vocabulary to define their love for each other, but that they certainly did not see it as part of a distinct identity, evidence of pathology, or indeed reason not to love, desire sex with, and marry women—and that goes for both Abraham Lincoln and Walt Whitman!

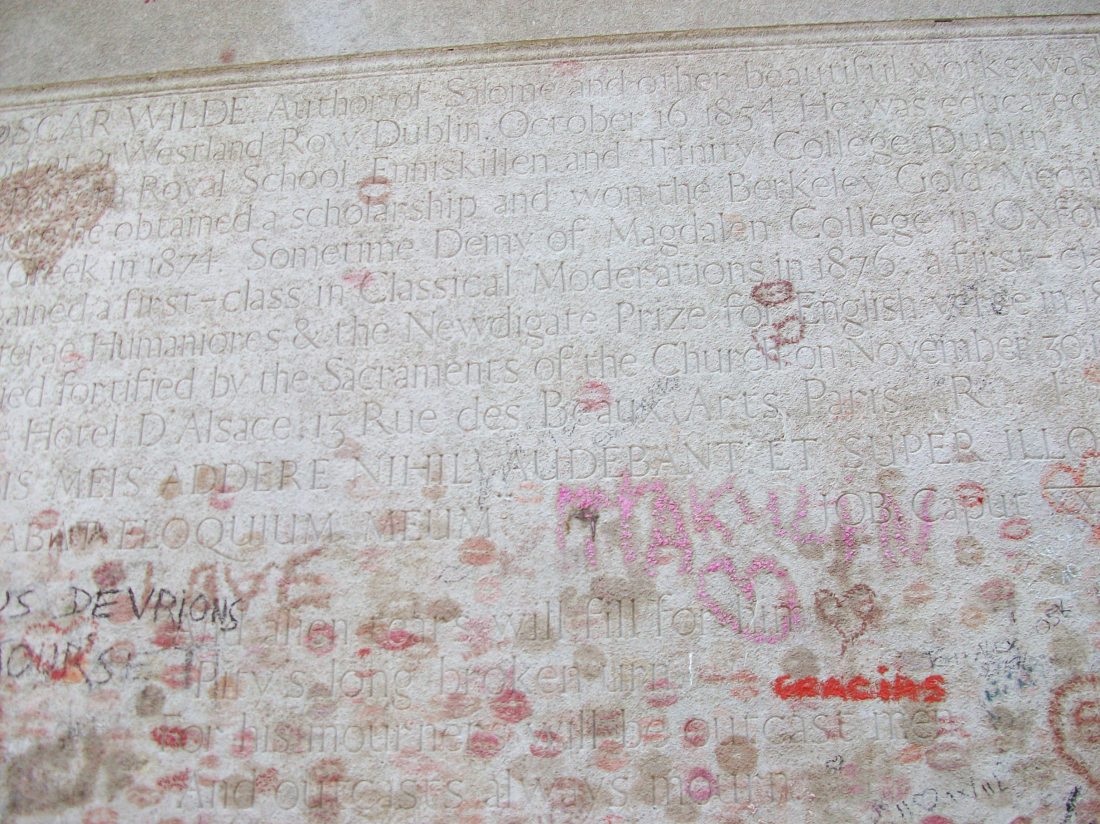

And so I’ve been getting myself in this “men before homosexuality were nothing like men after homosexuality” mindset, which is productive in that it allows me both to find Katz’s book very persuasive and to further my own thinking about what changed, theoretically and culturally, when homosexuality did emerge as an identity. But I found that easy suspension-of-my-own-sense-of-identity-categories challenged by the passage I quote above, simply because it does not sound like the experience of a man from before-homosexuality. It sounds like the experiences of young men from across the history of homosexuality (though particularly in its early history) who came to understand their sexualities as sexualities through the frame of classical literature and art. I titled this post the way I did because one of those men was John Addington Symonds, whose 1901 tract A Problem in Greek Ethics is about Athenian pederasty, and implicitly makes the argument that because Athenian sexual mores were different from late-Victorian Britain’s, there was no reason why Britain and its legal system shouldn’t change to accept himself and his fellow “Uranians” into the fabric of society (this was an argument Symonds certainly expressed in so many words in private, if not so explicitly in print). The secondary “Problem in Greek Ethics,” however, would seem to lie in Symonds’ adoption of ancient Greek sexual practices which do not map precisely onto modern homosexuality and would not have been considered “homosexual” then to seek cultural and artistic validation for a modern form of sexual deviance. This sort of essentializing is, it seems to me, in some sense endemic to being homosexual in the modern western world—and it is this sort of essentializing which Katz’s book fights against in part precisely because it is so endemic. (You know how academics are.)

And so to read about Albert Dodd’s bawdy Ganymede poem, and Katz’s observations about Dodd’s interest in Greek matters in 1837, far before the word “homosexual” enters the language or before the sundry proto-homosexual scandals of late-19th-century Britain get going, and to read them occurring out in the provinces, in New Haven, far away from the theoretical and academic and cultural work done to create homosexuality in London and Paris and Berlin, is to me to profoundly trouble the neat homosexuality-didn’t-exist-and-then-it-did narrative. It is to question what is homosexual and what isn’t, to challenge my coding of problems in Greek ethics as homosexual, and indeed to question Katz’s thesis (with which I otherwise agree strongly) about the mutability and historical contingency of identity categories. Is a search to understand one’s erotic impulses through ancient Greek literature something enduring across time, no matter what words exist in the language to describe it?

Blogger Historiann wrote yesterday about the importance of using “sideways” methodologies in building the narratives of people(s) and events (such as women, or people of color, or working-class people) whom written sources sometimes leave out. Sometimes these methodologies come with their own problems in ethics: Historiann gives the example of using the recorded lives of men in order to make inferences about the lives of women, but what does it do for women’s history if it’s still only told through the eyes of men? It seems as if the kind of work that Katz does moves similarly sideways, getting around the obvious lack of forthright records of 19th-century men’s sexualities by inferring and reading between the lines; I’m hoping to learn from his books how to employ similar strategies when writing my own thesis. But it seems to me as if there is always a tension between too much inference and too little (something else I learned from literary studies!), and that playing the inference game carries with it problems in ethics, Greek or otherwise. Am I undoing Katz’s work by assuming homosexuality on the basis of Hellenism? Or could he possibly be the one who is reticent to make a necessary logical leap. (What is truth, anyway?!)

This is a tricky business in which to get involved—and we should never lose sight of the concrete social and political ramifications our quirks of interpretation can have, when they make their ways beyond the ivory tower.

You must be logged in to post a comment.