That this blog appears on the first page of Google results for the search “platonic pederasty” (in quotes) will surely prove to be the crowning achievement of my intersession.

Category: LGBT

QOTD (2010-01-24); or, The Bloom of Youth and “all the joy, hope, and glamour of life”

Linda Dowling, Hellenism and Homosexuality in Victorian Oxford:

With this realization [that the “nonphysical eroticism of the Platonic doctrine of eros” was, basically, insufficient], Symonds comes to a bitter new assessment of his old teacher Jowett, as though Jowett’s Socratic “corruption” had somehow consisted in tempting suggestible young men down the delusive path to spiritual procreancy rather than fleshly excess. Writing from Davos in 1889, Symonds confronts his old tutor across a crevass of ancient and mutual misunderstanding into which the bitter sufferings of thirty years now pour. When young men in whom the homoerotic passion is innate come into contact with the writings of Plato, as Symonds now tells Jowett, “they discover that what they had been blindly groping after was once an admitted possibility—not in a mean hole or corner—but that the race whose literature forms the basis of their higher culture, lived in that way, aspired in that way…. derived courage, drew intellectual illumination, took their first step in the path which led to great achievements and the arduous pursuit of truth” (Letters 3:346). Symonds is making explicit here his sense of the cruel pedagogical contradiction within Oxford Hellenism which had harried him for so many years—his instruction in Platonic thought by the same teachers of Hellenism who denounced erotic relations between men as “unnatural”: “those very men who condemn him, have placed the most electrical literature of the world in his hands, pregnant with the stuff that damns him” (3:347).

And I mean, dude. Can you imagine being Symonds and discovering this? Well, maybe you can—maybe you, dear reader, have had realizations which are not dissimilar. But I am so, so very interested in this keen desire to, and profound experience of, discovering oneself in the classics—and then the notion that discovering oneself in the classics legitimates oneself. It could also work the other way around, though, as it did when Symonds and Edward Carpenter, among others, were just so eager to get Whitman to confess his own homosexuality (or whatever they would have called it)—knowing something about themselves, they were desperate to get some legitimation from respected authorities, regardless of whether the authorities themselves were likely to actually give it.

But, in the end, what I am most interested by is what an entirely different cultural moment we live in, because it is no longer a shock that idealized Platonic paiderastia should have a conceptual link to sexual practices, as it was (or so I understand) to some of those 19th-century intellectuals. In fact, in our time, it seems nearly impossible to unwind the two strands, and the only people who seem interested in doing so are those for whom the thought of “posing as a somdomite” is so terrifying that they work as desperately as they can to remove somdomy [sic for deliberate comic effect and the sake of allusion, obvs] from the picture. In our time, putting somdomy away in a proverbial closet such that it becomes mentally safe to conform to the Platonic ideal is something that comes from surely just as much a place of fear as that with which the young Symonds confronted his own sense of self reflected back at him from the pages of the “Greats”—only now the fear is called “homophobia,” and it’s a hard fear to pity when it acts to make some of our lives that much more difficult.

These are, of course, only absent thoughts, an entry in the 21st-century incarnation of a commonplace book, which is a segue into mentioning that I was glancing through Oscar Wilde’s own university commonplace book today, struck by how much more he knew and had read when he was just about my age. Never has the need to make room in my course schedule for Greek, for instance, seemed more pressing. At the end of an evening’s intentionally oxymoronic frenetic meander through the world of Victorian cultural history, and just a week before my twentieth birthday, what I am truly struck by is how young university-educated adults generation after generation, alumni class after alumni class, go through so many of the same thought processes, discoveries, adoptions and rejections of ideals, on the road to intellectual maturity. Some of us braid intellectual-cultural threads together, some of us undo the strands, and some of us step back and watch what happens. And all of us, I think, like the naïve young adults we are, are always surprised by the patterns that occur.

Historians and LGBT Rights

(cross-posted from my professional life at Campus Progress)

Perry v. Schwarzenegger, the federal challenge to California’s Proposition 8 led by star attorneys and former rivals Ted Olsen and David Boies, continued today with expert testimony from two historians of marriage, family, and LGBT history. Nancy Cott, a Harvard professor who specializes in the history of marriage and the family, and George Chauncey, a Yale professor who specializes in LGBT history, testified on the historical context of Prop. 8 and what American legal history has to say on the state’s involvement in marriage and in the lives of its LGBT citizens—which is quite a lot. Cott testified predominantly about how marriage is a dynamic institution which has changed over the course of American history, and which thus could change to accommodate same-sex couples as well; Chauncey’s testimony is still continuing since the court is on Pacific time, but so far he’s talked about the discrimination gays and lesbians have historically faced in America, going over some of the info he discusses in his award-winning book Gay New York, about that city in the pre-World War II period. (Full disclosure: I’m a serious Chauncey fan; I go all giggly and fluttery when his scholarship is discussed.)

As a history student, what this all demonstrates to me is the incredible relevance the study of history has to something like a court case—indeed, Chauncey first became famous for organizing the so-called “Historians Brief” in Lawrence v. Texas, the 2003 Supreme Court case which found sodomy laws unconstitutional. When a lasting American institution like marriage or, indeed, homosexuality is under discussion, the court needs historians to contextualize and interpret the present moment’s relevance to the historical narrative. You could even read the Prop. 8 proponents’ cross-examination of Prof. Cott this morning as a way of performing historiography: trying to get Cott to reinterpret what she’d said about the history of marriage to make it seem as if same-sex couples have less of a claim to that institution than her testimony had previously suggested. Of course, that didn’t happen, since the Olsen-Boies side knows what they’re doing, but it was interesting all the same.

What this further reminds me is that courtrooms are an awfully academic environment in comparison to grassroots protesting, ballot-box lobbying, and other forms of activism. For example, whereas these courtroom supporters of LGBT rights are positively relying on the expert testimony of historians, last week’s grassroots LGBT activists saw the expert testimony of historians at the annual meeting of the American Historical Association as a slap in the face of LGBT San Diegans, who have committed to a boycott of the hotel where the annual meeting took place.

Why this divide between the intellectualism of courtroom politics and the seeming anti-intellectualism of grassroots politics? (I read the San Diegan activists’ actions as a basic lack of belief in the relevance of, or perhaps misunderstanding of, what it is exactly that historians do.) I’m not sure—maybe some of you know—but I am interested to see whether the trial, which also includes testimony from a number of non-expert witnesses, will tell us.

In any case, it’s a constant reminder that LGBT rights is by no means a monolithic movement, and that each person who claims to be part of it may have radically different goals and angles for the movement.

On the AHA, the Manchester Hyatt, and Why the Modern LGBT Rights Movement Is Screwed

I read this article in my old wreck of a hometown newspaper, the San Diego Union-Tribune, and to me it represents many of the problems of mission and message facing the LGBT rights movement as it enters another decade. Excuse me briefly while I blockquote extensively:

Waving signs reading: “We All Deserve the Freedom to Marry,” more than 200 gay-rights activists and union members representing hotel employees rallied outside the Manchester Grand Hyatt on Saturday in the latest protest over the owner’s support for a ban on gay marriage.

The protesters banged on drums and waved rainbow flags while chanting “Boycott the Hyatt — Check! Out! Now!”

The rally targeted the American Historical Association, which decided to hold its annual conference this week at the Grand Hyatt despite an ongoing boycott.

About 4,000 association members — a tweedy mix of college professors, history teachers and librarians — are attending the conference that organizers decided to hold rather than pay steep cancellation penalties.

[…]

Marie McDaniel, 30, from the doctoral program in early-American history at the University of California Davis, said she regretted that moving the conference elsewhere wasn’t an option.

“I think that while many historians are in support of (the boycott), it would hurt them more than the hotel,” she said, “so they decided to do what historians can do, which is increase dialogue.”

McDaniel said she gave a presentation on intermarriage in the 18th century, showing the evolution of attitudes about such unions. For example, she said, German Lutherans used to marry only within the faith, but eventually some married Anglicans and “that was no longer seen as so awful,” she said.

[…]

Lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender groups started the boycott. Local unions have their own disputes with Manchester over labor issues at the nonunion hotel, which has 900 employees. The unions object to what they describe as excessive workloads for housekeepers; they also want to ensure job security if the hotel eventually is sold.

Commerford contended that the unions just want money, estimating that the hotel-workers union Unite Here would get $2.2 million a year in dues if the hotel were organized. He said the workers don’t want a union and noted that the housekeepers have a 4.5 percent turnover rate, much lower than the industry average.

Cleve Jones, who works with Unite Here and has been active in gay-rights advocacy, said the boycott won’t end until certain demands are met, including a public apology from Manchester and labor concessions.

“The solution is for Mr. Manchester to sit down with the community,” Jones said. “There is no one single demand to end the boycott.”

There’s a lot going on here, but I’m going to try to keep it simple.

1. It was wrong for Jones, Unite Here, and the California marriage equality groups to target the AHA. The historians have made it perfectly clear that they booked the Hyatt in 2003, which (if you’re keeping track) is quite a long time before either Prop. 8 or Manchester’s record on labor issues became clear. Had the historians cancelled the reservation, they would have had to pay $600,000 to the hotel—more money in Doug Manchester’s pockets, which is obviously the exact opposite of what’s ideal here. The AHA reportedly devoted more sessions this year to anything even tenuously related to marriage equality or LGBT rights than they have in their entire history. That’s a victory of a different kind for queer and family historians, and it’s worth noting.

2. Technically speaking, the historians were not violating any great ethical standard by going ahead with the conference. The San Diego LGBT community boycott on the Hyatt is an unofficial institution that probably very few people outside of the San Diego LGBT community know anything about; what’s more, it became official as of Pride 2008, and so the AHA booking predates the boycott. What’s more, there was no picket line to cross until the Cleve Jones camp decided to put one there. There was some shaming of historians who would choose to cross a picket line to go to interviews in the Hyatt, but that’s a highly unfair and undeserved position in which to put the historians, who have gone out of their way to rectify this situation.

3. Now, let’s think about who on which side of this conflict is doing more to further the cause of LGBT Americans. Is it the likes of Cleve Jones—who became famous again because some folks made a movie about his mentor and he was played by Emile Hirsch—who decided to protest, to be fair, a legitimately evil institution in San Diego on the day that some thousands of historians happened to be there, or is it the historians, who devoted a disproportionately large segment of their annual meeting to discussing the history of marriage, despite the fact that marriage is not the only issue facing LGBT Americans today?

Yes, Doug Manchester is evil. Yes, there are reasons not to book your San Diego vacation there. But instead of hating on the historians, maybe the San Diego LGBT groups should consider what the historians are doing to remember their movement, to contextualize their movement, to keep the knowledge of what they’ve done for the past forty or fifty years alive and to understand how an interconnecting set of factions have worked together. The historians have done the research—they’re going to be the ones telling you just how necessary it is for marriage equality to be the be-all and end-all of LGBT rights. And they’re going to be the ones telling you—as I, proto-historian, am telling you now—that Prop. 8 happened. It sucked. But it’s over, and it’s time to move on. It’s time to get over this petty tug-of-war about state-by-state marriage, and to focus on the things that will actually change people’s lives, actually make them equal in practice.

Listen, SD LGBT groups, I’m from San Diego. I volunteered for the No on 8 campaign, I went to the rallies and protests after it, I’ve stood on University Avenue in Hillcrest and watched the Pride parade go by. And I’m telling you that this is the wrong fight. Maybe you should look to the public schools in your city, where queer kids aren’t safe (and yes, I’ve been there too, and there was a reason why I know so many queer kids who dropped out or went to school across the city or across the country). Maybe you should take an interest in immigration issues, and try to keep together cross-border couples who, while they can’t get married, still would like to stay together. Maybe you should to AIDS work, or work with queer homeless people. Maybe you could even look outside of your city and outside of your country, where being gay carries a death sentence. And if I were Equality California and I were strategizing about whom to pick a fight with, the American Historical Association so wouldn’t be it.

Historians are your allies, San Diego queers! You need them—us!—to remind the kids who didn’t know that there was an LGBT rights movement before Prop. 8 that others have fought for issues besides marriage before them. Frankly, unless this movement sharply reevaluates itself, and decides to try to work on life-and-death situations instead of throwing a hissy fit at the AHA, I don’t know what hope in hell it has of achieving success in the so-called civil rights battle of our generation.

Untold Stories; or, You’re Probably Sick of Hearing Me Talk About Gay Men By Now

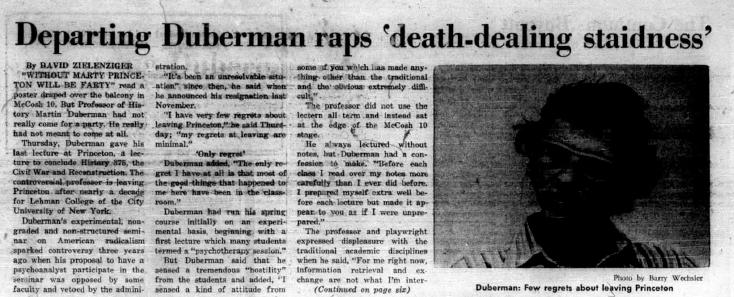

I’m doing a project for a class about Princeton and race and campus planning and things, and it’s involved a lot of archival research. This is great, because I actually really love archives—particularly when, by chance, they lead me to totally unrelated gems like this Daily Princetonian article from May 1971:

“Departing Duberman” is Martin Duberman, founder of the CUNY Graduate School Lesbian and Gay Studies Center and one of the seminal figures in queer scholarship. But you wouldn’t know that from reading the Prince article, which frames Duberman as a fairly classic child of the Sixties, whose “experimental, non-graded and non-structured seminar on American radicalism” befuddled the Princeton establishment, and whose students “had criticized him for his informality and call for spontaneity.” The article quotes Duberman, too, who appears to make no mystery of his departure to CUNY, saying, “Staidness is the best summary word for my experience at Princeton and it symbolizes what Princeton has always stood for.”

“Staidness,” however, is a pretty nonspecific word, and a glance at Duberman’s 1991 memoir Cures (the title refers to alleged cures for homosexuality) fills in some of what he might have meant when he used it. (I would like to note at this juncture that if I have any useful knowledge, knowing the queer shelves in Firestone well enough to find Duberman’s books without a call number appears to be one of them.) The prologue to Cures refers to Duberman’s time at Princeton in the ’60s, expressing his frustration at outdated attitudes to women and African-Americans, and a hostility towards radicalism or really anything different or threatening. But, gesturing towards the subsequent material in the book, this is how the prologue ends:

My private world was not nearly so comfortable [as my students’]. I lived in faculty housing—a small pseudocolonial unit built to sit “picturesquely” next to an artificial pond—and my personal life was a neat match for the antiseptic surroundings. Except for one local pub where ambivalent glances were rumored to have been exchanged by men awaiting their turn at the dart board, and the town of New Hope, about an hour’s drive from Princeton, where a gay bar was actually known to exist (though subject to police raids), the only other hope for contact was in the bushes and the men’s room at the Princeton railroad station, dim prospects in every sense. Even if Princeton had offered more opportunities, I would have been ambivalent about taking advantage of them. In these pre-Stonewall liberation years, a few brave souls had publicly declared themselves and even banded together for limited political purposes, but the vast majority of gay people were locked away in painful isolation and fear, doing everything possible not to declare themselves. Many of us cursed our fate, longing to be straight. And some of us had actively been seeking a “cure.” In my case, for a long time.

Of course, the Prince would hardly report this, because Duberman would hardly have said any of this in 1971. It’s a useful reminder of the apparent insurmountability of piecing together the history of a community that is not a community, and how much goes unmentioned when there’s not an accompanying memoir against which to fact-check.

On Larry Kramer, and Doing History

I think of myself as a pragmatist when it comes to most kinds of action and activism, more conservative than I think many people perceive me to be. And yet there is much, all the same, that I find resonates in Larry Kramer’s point of view:

Temperamentally unsuited to ceding the pulpit, he has never accepted the national gay organizations as competent advocates for gay people, and, in the wake of New York’s failure to pass a same-sex-marriage law, can only repeat his contention that state-by-state incrementalism on such matters is “a waste of time.” If it depresses him, that’s because it’s personal: “I can’t afford to wait for gay marriage in ten years!” he moans. “Unless something radically changes, I won’t be able to leave my estate in any sensible way to David, and everything we built up together suddenly won’t be there to support him. That’s criminal.”

I have been learning a lot more about ACT-UP recently, forcing myself to confront my trepidation and depression at delving into the history of the beginnings of the AIDS crisis. I more and more feel as if it is my duty to learn this history, and be able to relate it—perhaps even more so than it is my duty to learn and teach to the next generation the history of queer identities, cultures, and communities more generally speaking. As I do so, I find myself understanding why and how pragmatism is not always equal to caution. I find myself crediting radicalization with not only feeling good, but actually getting shit done—though I also find myself realizing that, as with all historical narratives, things are more complicated than it is possible to explain in any space less than that between the covers of a book, if then.

If you read that New York magazine profile I linked to above, you’ll see that Kramer is at work on a 4,000-page gay history, not just of the times since people have begun to call themselves homosexual, but of the times before that as well. For once, I do feel informed enough to say that I’m skeptical of that approach. It’s one that appears to reside in double entendres and guesswork, in superimposing the attitudes of the 20th century on earlier eras, and it’s not (I find myself presumptuously thinking) the right way to be sweepingly radical. Yes, the history of American queerfolk is still in the process of being told. Yes, we could use a definitive textbook of American queer history. But the subdiscipline is still in the process of defining itself, and the “everyone is gay” approach has nothing more to recommend itself than the “no one is gay” approach. Maybe it could be a clever commentary on historiography’s heterosexism—but maybe it’s really just bad history. In this profile, Kramer’s conviction that Abraham Lincoln was gay reads like a conspiracy theory, and an allegation difficult to make with respect to a man who died before the coinage of the word “homosexual.”

I of course do not mean to deride Kramer’s contribution to anything, and in fact I have kind of a knee-jerk reaction to the people who do. ACT-UP is evidence that we need radicalism alongside moderation to get things done, that the two work together, that factionalization can (as Amin Ghaziani says) sometimes be productive. The fact that Kramer was, apparently, left out of the recent Harvard exhibition about ACT-UP is, to the best of my knowledge, ahistorical and unfair.

But I read these stories, and I take from them lessons on how to do my own history. When you tell a history, you should not be creating it out of whole cloth—but then how to tell it without creating it, without imposing a 21st-century lens upon a cultural context you may only after years of research begin to understand as natively as you do your own?

Larry Kramer, I have the utmost respect for you, but you have given all us proto-historians (or, well, this one, anyway) an object lesson in “pitfalls to avoid when doing gay history.”

QOTD (2009-12-16): Missed Connections and Poignancy

I never got into reading the “missed connections” sections on Craigslist or anywhere else—but as of a few days ago, Princeton acquired its own, and now I’m transfixed. There’s something about knowing the locations and the events and the culture driving, to a certain extent, all the postings that makes them that much more engrossing. Of course, I’m particularly struck by the postings listed as male seeking male or female seeking female—postings like this:

Frist

male seeking male – posted about 1 hour ago

I always see you walking around Frist. Tall, handsome, nice glasses, very well-dressed, you even had a purple scarf on once. Are you…different? Let me know.

Reader, what a flashback to another era. “Are you… different?” What a strange question to ask in 2009, when the word “gay” and the acronym “LGBT” grace the front pages of our newspapers and the internet has educated the overwhelming majority of all of us. What a seemingly unnecessary anachronism.

But the fact it was asked, of course, suggests to me that maybe the euphemism is not an anachronism, and maybe in this particular place and time and culture it’s still necessary. Of course, that’s in some ways problematic, and in some ways speaks to the ghettoization and marginalization of the Princeton queer community; it speaks to how many people here are still in the closet. But as you might know, I have a passion for the language of secret codes, of double meanings, of hidden significances, that once characterized a largely underground culture. And although I am sure there are few people reading Princeton missed connections who won’t draw the same conclusions from “different” that I did, this anonymous posting into the void is so weirdly reminiscent of so many others of years past, long before there was an internet on which to post such things, back when there were only word of mouth and nonvocal signals and maybe if you were lucky a gay paper or magazine.

I am reminded, once again, that just when you think times have changed… they haven’t.

NJ: CALL YOUR STATE SENATOR NOW!

What’s up, New Jersey? Did you know that your state senate is going to be voting on marriage equality tomorrow? And do you know what you can do to make sure that your state senate passes marriage equality? It’s so easy: the best, most constructive thing you can possibly do is to call your state senator and urge him or her to vote yes on the marriage equality bill.

If you don’t know who your senator is, you can find all their names listed by town here. And if you live in Princeton (since many of this blog’s readers do), your senator is Shirley Turner, who is as yet undecided about her vote and whom you should ABSOLUTELY call. Her phone number is (609) 530-3277 and there is no reason you shouldn’t pick up the phone and call her office right now.

Be sure to let your senator know if you belong to a demographic which would be personally affected by marriage equality, or if you belong to a demographic that’s supposed to oppose marriage equality. So if you’re a person of color, tell your senator. If you’re Catholic, Evangelical Protestant, Mormon, or Orthodox Jewish, tell your senator. If you’re a member of the clergy in any religion, tell your senator. If you’re a registered Republican or otherwise identify as conservative, but still support marriage equality, tell your senator (especially if your senator is a Republican too!). And, of course, if you’re LGBT, if your friend or relative is, if you have two moms or two dads, if you would really actually like yourself and all your friends and loved ones to have the same rights as each other and if you believe in justice for all, then call the New Jersey state senate and let them know that.

If you’re a resident of New Jersey you have absolutely no excuse to refrain from calling your senator today. It takes all of two minutes, so procrastination is not an acceptable excuse, nor is being too busy. If you’re not registered to vote in NJ, or if you’re not an American citizen, that’s no excuse: by virtue of living in NJ, your state senator represents you and your needs, too. You don’t even have to believe in the importance of the issue of marriage: this bill’s passage will be symbolic, and it will turn the tide in a disheartening fight for civil rights. Picking up the phone, calling your senator’s office, and talking for 30 seconds is the single most important thing you can do to make it possible for New Jersey to become the next state to stand up for equality.

Methods of Mourning; or, Tying Together the Disparate Strands of a School Day

Today at lunch, a friend continued with me a conversation we had started to have online last night. To paraphrase, he was telling me about what he finds inspiring in the worldview of the Old-Testament prophets: these people, my friend said, believed that the smallest injustice was worthy of our attentions, and as valid a point of concern and moral attention as a large-scale conflict, or one to which society imparts greater weight and importance. Without having enough exposure to the Bible to know much about this school of thought, I told my friend I thought this was a morally valuable attitude, but a risky one. If we focus on every injustice, I told my friend, we risk self-annihilation. We risk becoming swallowed by a world of things to fix, and losing our identities and our senses of self in an avalanche of problems and traumas and tragedies. We risk not being able to function as productive members of society, because we can do nothing but be overwhelmed by how many of the reasons that the world is going to hell in a handbasket—and many of the problems which individual members of a society face on a daily basis—are outside of our control.

I didn’t explain this in the context of the conversation, but when I responded that way to my friend, I was of course coming from an intensely personal perspective. The past few months for me have been a struggle at balancing negatives and positives, at knowing when to celebrate and when to fight and when to mourn, at coming to terms with my decision that, in fact, it is important to be a cohesive individual with a set of ideals and principles and morals and desires and reasons for being—and that, what’s more, a person’s state of being is more than a collection of these things. I believe I have some experience with the dangers of being consumed by problems. At risk of being melodramatic, I’d argue that I grapple daily with whether it is as worth my time to better myself or to fulfill my own desires as it is to fight for some external cause. Now, I don’t believe in any sort of “virtue of selfishness.” That’s the farthest thing possible from my mind. But I do believe there is some value in self-preservation, in identity-preservation, in soul-preservation. I have to. I have to believe that I, as an individual, matter; that my rights to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness matter in the same way as those of someone who is beset by far greater inequalities and injustices than I am. Ego humana sum, to make an emphatic point by butchering Latin—maybe this is just the voice of the latent conservative in me whom I always suspect is lying in wait, but altruism (and I mean “altruism” in a positive sense) is not always my direct route to pleasure and fulfillment. Isn’t it morally defensible to balance self-fulfillment and other-fulfillment? I would argue that it is, and I would further argue that it is impossible to do so without compartmentalizing. Compartmentalizing is an ugly thing, but it is a survival tactic. It’s a way to get through the day and a way to sleep at night, a way to survive until the next day so that you can continue to develop your own self and continue to take on projects and perform actions that will further the elimination of inequality and injustice. If that makes any sense, it was the subtext of how I responded to my friend at lunch today.

Today was an appropriate day on which to raise this issue, subtext included. In my English class this morning, we discussed Sylvia Plath’s poetry, and if there is any art which is awash in the presentation and examination of particularized personal trauma, well, it’s Sylvia Plath’s poetry. I am not by any means qualified to discuss poetry; I feel in over my head in most of this class’s lectures and discussions. But I was enormously fascinated by my professor’s argument that Plath fundamentally altered the way we understand the genre of elegy—in fact, said my professor, she wreaked havoc upon it, smashed it, and turned it inside-out. By Plath’s later poetry, her elegies are not reverential, they are furious. She made it acceptable, said my professor, for successive poets—particularly women poets—to write elegiac poems that incorporated not the classical, reverential emotions of lamentation, praise, and consolation; but an anger and a frustration and even scarier actions like (to use my professor’s terminology again) desecration and annihilation.

My thought, in the context of developing my own juvenile philosophy, is that Plath’s smashing of the elegy, her pulverization of the memory of her father through that elegy-smashing, and, in the end, her own tragic self-annihilation, are some of the risks of being so fully consumed by mourning. My professor said that Plath characterized her reactions to her father’s death as a primary source of her poetic inspiration: what happens when your whole life revolves around mourning, revolves around confrontations with tragedy, trauma, and injustice? Again, I’m a rank amateur, but it seems to me as if Plath’s example suggests that you may be consumed—and destroyed—by the mourning.

Because of one of my chosen subfields of study, I find myself running up against elegies with some reasonable frequency. I am fascinated by how queer individuals have, over time, constructed community and culture, and how the values of community and culture interact in this historically marginalized group. There is perhaps no better example of these patterns than the outpouring of artistic expression that occurred at the onset of the AIDS crisis, as the decade turned from the 1970s to the 1980s—and continuing well into the 1990s. As far as I can understand it, for some gay writers and artists and musicians and theorists and other producers of cultural material, making art and culture that grappled with AIDS was a way of forming community around—collectivizing—uniting—a series of individual traumas and tragedies each important as the next, which, when taken together, became a grave human crisis. I look at this cultural outpouring and coming-together—represented in forms as diverse as Larry Kramer’s plays, Nelson Sullivan’s films, and dozens upon dozens of memoirs and indeed elegies—and I see an instantiation of the ideal which my friend raised. In this art (at least, when I read it), every death, every individual struggle, becomes both important in and of itself, and important as a constituent part of a historical and cultural moment. Another metaphor is Cleve Jones’ AIDS Memorial Quilt: each constituent part of that quilt is important in and of itself, no more or less important on the basis of why it is included in that quilt. These are all elegies, and they are all particular, though perhaps—it’s hard to say—they avoid the risks of subsumation which the Plath seems to illustrate.

I am fully aware of the fact that I have no right to talk about this kind of elegy. This particular genre of collective mourning is one of which I, who was born in 1990, have no possible conception. Today, of course, is World AIDS Day—and I have struggled for the past week to think about whether I have anything to say concerning a crisis which I tend to historicize and yet is fully contemporary; a crisis whose onset and whose particular tragedies I did not and have not witnessed. And yet I have chosen history as my path towards understanding these moments of crisis, and I believe that I do have a duty to understand them, and to do what I can to further the telling of these stories. If each injustice, each death, each singular struggle is a legitimate subject of our attention—and our elegies—it behooves me as someone who wishes to learn to be a historian (but it also behooves all of us) to try.

After the exchange with my friend about Prophets and particular problems, lunch passed without mention of mourning for the victims of life and death. Lunch passed in lightness and brightness, in the silliness that ensues when good friends share a table and a conversation, and when I finally tore myself away I hurried to class across a quad awash in sunlight. I caught myself suddenly joyful: excited for my class, delighted to be moving from one space I enjoyed to another, across the bright and beautiful and green quad. I slowed my pace for a few minutes (this, it should be noted, made me late to class, and earned a sarcastic comment from my professor), and I wondered: why am I seizing this joy? Why am I brushing aside the weight of undeserved deaths to be made happy by something so ridiculous—and so absurdly self-interested—as walking from point A to point B in nice weather?

Well, reader, I think I know why: it is because the task of elegy is an enormous one, a terrifying one, a profoundly disturbing and troubling one. It is because life is not worth living, and death is thus not worth confronting and mourning, without the promise of truth through beauty. And it is because somehow, in some way, we all have to take the threads of our work days, and the knowledge we have gained in them, and the conversations we have had throughout them, and braid all those threads together into a strand which is somehow strong enough to let us fall asleep tonight, so that we can wake up again tomorrow and go about making the world—and ourselves—worth continuing.

Books I Would Buy If I Hadn’t Promised Myself I Would Stop Spending What Little Money I Have on Books

Linda Dowling, Hellenism and Homosexuality in Victorian Oxford

Martin Duberman, Cures: A Gay Man’s Odyssey

Robert Corber, Homosexuality in Cold War America: Resistance and the Crisis of Masculinity

Clearly I need to stop dallying by the Gay and Lesbian Studies section in Labyrinth all the time.

You must be logged in to post a comment.