I found it rather silly that this ad came up on my Facebook yesterday:

Category: Personal Life

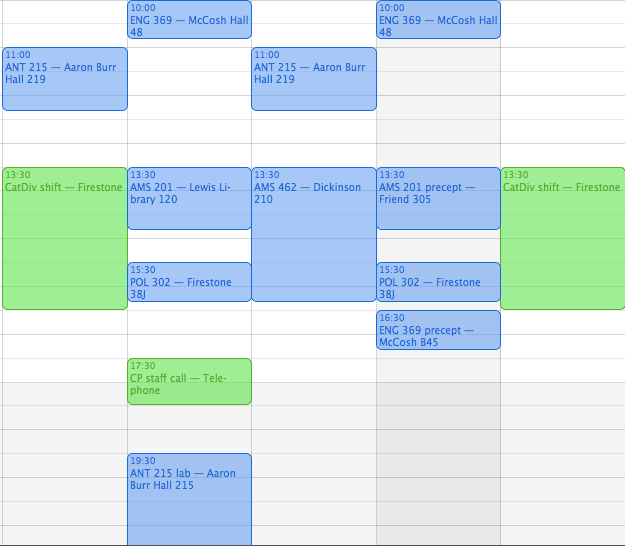

Course schedule

In Which Rachel Maddow and I Have Something in Common

Jason Mattera (of kicking your faithful correspondent out of the Young America’s Foundation conference fame) didn’t limit his comments about his political opponents’ physical appearance to the Campus Progress editorial intern with a relative lack of power or social capital who wanted to cover his conference this past summer. He also thinks he’s going to win back conservatism’s power by making remarks about the appearance of one of the most popular news hosts on TV, as Sarah Posner reported on Monday:

But targeting Millennials through pro-life appeals mixes sexuality with chastity. During the panel, Mattera took the David and Goliath metaphor another perverse step: If conservatives (David) smite liberals (Goliath), they will be rewarded with the hot conservative women, just like King Saul promised his daughter to the warrior who slew the evil giant. “You know his daughter must have been beautiful because there’s no guy whose gonna die for an ugly girl,” Mattera chortled. “Our women are hot. We have Michelle Malkin. Who does the left have, Rachel Maddow? Sorry, I prefer that my women not look like dudes.”

Mattera, who doesn’t seem to see the inherent problem with criticizing women’s appearances instead of their ideas, responded on his blog:

Okay, okay. I’ll admit it: Not all lib women look like dudes. I’m sure there are some who don’t. Maybe. But folks, can we at least agree on Rachel Maddow? Some bipartisanship, people?

Posner refers to the college activism panel that I participated in at Family Research Council’s conference over the weekend. What did hot women have to do with my talk? Not much, actually, despite Posner making it the basis of her piece. It was just a casual reference—me noting that even if I weren’t an activist, I’d probably still wander to the conservative camp because our women don’t look like the picture [of Maddow] above.

Rachel Maddow is an extraordinarily talented and successful woman, and it’s not too often that I get to be in the same category as her, so I’m sort of perversely excited that Mattera thinks I’m as worth calling a guy as Maddow. Seriously guys, I’m milking this for all it’s worth.

But what I find interesting and puzzling about folks’ reaction as I’ve told them about this is how eager they’ve been to assure me that Ms. Maddow is incredibly attractive, or that conservative women aren’t attractive, or to insinuate that the fact that Mattera put me in the same category as Maddow says something good about my physical appearance. I’m interested and puzzled because I would have thought the answer to this would be to challenge Mattera’s (and the conservative movement’s) sexism. This conversation shouldn’t be about which side of the aisle has the nicer-looking women. This has nothing to do with “Newsflash! Dykes can be hot too!” This has to do with the fact that we all—Maddow, Mattera, myself, Michelle Malkin, and everyone—should be judged on the basis of our ideas, not our appearances.

I think there are plenty of interesting things to be said about how confused the conservative movement (as represented by Mattera) seems to be about engaging with women on an intellectual level. Mattera seems rather challenged by the notion that women could contribute more than their appearances to the political sphere, and doesn’t even address the ideas of the women on his own side. It’s as if we’re mascots in his universe, and that speaks volumes about what his universe consists of and how he interacts with it. That’s a social phenomenon we could analyze at great length if we wanted to.

But I really have too many other papers to write to bother with unpacking that one, and I think maybe our time could be better served in the long run by not letting Mattera make this a discussion about physical attributes. Yes, it can sometimes be challenging to sit there and watch someone make sexist and implicitly homophobic comments about you, without challenging him on his premise. But if we don’t void the premise entirely, we’re not going to get anywhere. I think I’m going to focus on hoping that one day Rachel Maddow and I will have something in common that isn’t the length of our haircuts.

UPDATE: Ironically, Maddow has one of the best summing-ups of this whole “conservative movement” thing.

In Which I Lose My Patience; or, The Princeton Social Scene, Continued

Yes, I (very clearly) enjoy two-clause post titles. At this point, I think you’ll just have to cope.

The Princeton University Press Club is a long-standing institution that has made the names of more than a few professional journalists. They have a slightly less long-standing blog which occasionally picks up an interesting story not covered by the Prince, but which more often than not is really quite fatuous. I’m sure all the writers are solid reporters for the local, state, and national papers where they string/intern, but on the blog, quite a lot of them are frequently guilty of either not understanding snark or of assuming that everyone on campus comes from a privileged background and thus fits totally seamlessly into a dominant culture that further privileges privilege. The most recent offender, wherein the author argues that Princeton’s twice-yearly bacchanalic prepfest isn’t alienating at all:

Lawnparties was never really about the band. It’s a wonderfully weird celebration of Princeton, honoring both what it is and what it could be.

Yes, Lawnparties is an anthem to the Princeton stereotype – loud music, louder pants, drinking before 10 a.m., and preppy bacchanalia. But it’s not just day drinking that makes Lawnparties a special day.

For all its elitist trappings, Lawnparties is Princeton’s egalitarian party. For one day, it doesn’t matter who you know, or what club you’re in. For one day, the bouncers don’t care if you’re on the list, or have two salmon passes. If you go to Princeton, for one day the eating club lawns are your lawns. Seniors and freshman stand shoulder to shoulder in the sun, drinking warm champagne and rocking out to Journey.

The writer of this post, of course, misses the key point that letting anyone listen to a band in the backyard of a usually-exclusive bicker club is only an act of egalitarianism if someone who is usually barred admission from said bicker club fits well enough into the culture to feel welcome there once admitted. Thinking this while reading, I got frustrated enough to comment on the post:

Egalitarian? Since when? Lawnparties elides the stratification between bicker and sign-in, between the haves and have-mores, the populars and the more-populars. But it doesn’t do anything to include people who don’t own a single pastel Lacoste polo or sundress, who don’t like to get shitfaced, or who for a variety of other reasons are just disgusted, not entertained, by the preppy Ivy League stereotype. Believe it or not, 30% of this university’s juniors and seniors aren’t in an eating club. And for many of them, all the clubs could be on PUID and they’d still feel like losers and outcasts. For some of them, Lawnparties is an excuse to go out of town for the weekend, or else an insufferably hot weekend spent indoors with all the windows shut, trying to drown out the sounds of someone else’s party to which, supposed “egalitarian” nature aside, it’s still perfectly clear that those who don’t conform aren’t invited.

Last spring, I went and sat in the basement of the library to work during Lawnparties afternoon, knowing that I would feel awkward and miserable and outcast if I dressed up and went down to Prospect Avenue to stand in a yard getting drunk, but also knowing that if I could hear the strains of Lawnparties music from my room, I would be so tortured by my outcast status that I’d be unable to work. This past weekend, a trip I’d planned happily coincided with Lawnparties weekend, so that I didn’t have to watch debauchery going on all around me to which I am implicitly not invited. Instead, two friends and I high-tailed it to Rhode Island to visit another friend, and I had perhaps one of the best weekends of my life. (While I am given to hyperbole, this is not hyperbole. At all.)

If it hadn’t been for Princeton, I wouldn’t have met the friend I was going to visit, nor the friends I made the trip with. If it hadn’t been for Princeton, I wouldn’t have managed to parachute into a subculture that isn’t interested in what the rest of Princeton is doing Lawnparties weekend. This school has a lot screwed up with its culture, but it also gives you the tools to subvert that culture, the resources to make your own choices, and of course some of the best academics in the world that you can take solace in whenever (if you’re like me) your essential state as a loner can get just a little too depressing. And that’s why I’m a Princeton evangelist, and why I care enough about Princeton to invest my time and efforts in making it a place where I and people like me are as much at home as the people who feel like Lawnparties is the great equalizer.

But for all that to work, the people who feel like Lawnparties is the great equalizer need to realize that although they are the dominant force in Princeton social life, they are not the only force. They need to realize whom they’re alienating and whose insecurities they’re reinforcing. They need to recognize that they speak for a world of privilege and social posturing that is inaccessible, undesirable, or flat-out disgusting to a lot of people with whom they share a campus.

And with that, it’s back to work: I have to read Rousseau’s Discourse Concerning Inequality for tomorrow.

Mary Travers

Celebrities die seemingly every day, but I was enough of a nerd that those who do didn’t have a formative enough influence in my life that I’m really affected by their death. Mary Travers of Peter, Paul, and Mary is a different matter. She died today, the AP says, and I feel bereft, because she’s been a reassuring presence over the past few years. She and Peter and Paul would play a concert at Carnegie Hall, or occasionally even put out a new album, just to let us know that they were there, that they still cared, that they were there making their slow way through the Bush years just as we were. I have their 2003 album In These Times, whose title alone says enough about the sociopolitical context in which it was released. And it can’t have been too hard for Peter, Paul, and Mary to reopen the floodgates of song, as experienced as they were with performing to audiences marching against Vietnam. But when there is an anger and a sadness and a fighting spirit to their music, there is also innocence and whimsy and play—we learned and sang some of their songs in my Montessori preschool class. One of their albums, a cassette that we often played in the car when I was little, contained both the sweet, childlike “The Garden Song” and Woody Guthrie’s migrant workers’ anthem, “Pastures of Plenty.” They sang songs by Tom Paxton, by Guthrie and Seeger, by John Denver. They quietly incorporated progressive Christian themes into some of their music, particularly later in their career, but it would have been impossible for our atheist household to find fault with their themes of unity and friendship and love.

I always thought it was Mary who got the best parts in the group’s three part arrangements. She sang melody more often than harmony, and when the three would take turns singing the verses, she always got the best ones. She sings lead on “Pastures of Plenty” and “Leaving on a Jet Plane.” Her verse of “The Times They Are A-Changin'” is my favorite: “Mothers and fathers throughout the land/Don’t criticize what you can’t understand…” She often gets a verse later in the song, I think, the one at the critical juncture of the lyrics’ plot. In “Puff the Magic Dragon,” she sings the verse when Puff realizes Jacky is gone forever. It’s arguably the most important verse in the children’s song that is so much more than a children’s song, which says so much about the loss of innocence that was the second half of the 20th century.

If you’re listing “Peter, Paul, and Mary,” Mary comes last. It was never “Mary, Peter, and Paul.” But her voice stands among those of Joan Baez and Judy Collins and Joni Mitchell as belonging to one of the strong women of conscience who popularized the antiwar songs and union songs and above all songs of a mass cultural movement written by less accessible folk artists. Mary Travers’ voice is instantly recognizable, and even though it’s a mellifluous alto, it always rises above those of her male colleagues. It’s strident. It’s beautiful. It believes in something.

I’m part of a group at school that gets together once a week to sing together: folk, country, blues, that sort of thing—anything that’s found in this book. We sing more than a few songs Peter, Paul, and Mary popularized—some of our favorites are “Puff the Magic Dragon” and “Marvelous Toy.” We’re not a very political group, and most people didn’t grow up singing left-wing political music like I did. My attempts to teach the union songs and peace songs Peter, Paul, and Mary sing haven’t always gone over well. But I guess it’s just as well, then, that Peter, Paul, and Mary have had songs for every occasion, every mood, every political moment.

Here’s one of my favorite songs in the whole world, “If I Had a Hammer.” Now I’ll shut up, and you’ll watch that video. And listen to that Mary Travers’ voice. And see how much she believes what she’s singing—as may we all.

In Which I Get Defensive About Princeton

The higher ed blogosphere has said most of what needs to be said about the latest take on the college-rankings phenomenon, GQ‘s “America’s Douchiest Colleges” list. But something I think hasn’t been mentioned is that this list, like most of the other rankings out there, probably wouldn’t exist if it weren’t for pre-existing stereotypes that get reinforced year-in, year-out about America’s most name-recognizable colleges.

While I’m aware that going where I’m about to go may only serve to undermine my entire argument, the only way I know how to discuss this is by speaking to my experience. So.

Take, for example, my college. I go to Princeton, which has a high level of name recognition. It’s been around for a while, and it’s got a reputation among most constituencies you ask about it. Among people who write college rankings, and people who pay attention to them, Princeton is hard to get into (you have to be smart, and have high test scores, among other things), and its alumni get access to high-paying careers on the basis of that aforementioned name recognition. These are things some college applicants want out of a university (the prestige of selectivity, a financial return on the tuition investment), and this popular perception influences why Princeton continues to score highly on metrics like those used by US News and Forbes, and why other universities will rate Princeton well in the all-important US News peer surveys.

Many other people who perceive this exclusivity and elitism see it as a bad thing. They criticize Princeton for being “preppy,” for privileging further the already privileged, and for reinforcing a culture that’s desperately out of sync with “real” America. Some of these people who are critical do have an accurate picture of things that could be improved upon to further diversify Princeton, or to change the ways its admissions and financial aid policies operate to make things more equitable. There are huge improvements to be made in this regard: for example, one recent survey of students’ backgrounds and attitudes showed that those who come from financially well-off backgrounds are much more likely to join eating clubs, which are a central aspect of mainstream Princeton social life. That’s a problem—and, it should be noted, the university administration is working to fix it by offering financial aid that makes it no more costly to join an eating club than to opt for a university dining contract. (For the record, though I disapprove of the eating clubs that choose their members by a selective, competitive process, I don’t see a problem with the ones that use a nonselective process. However, I don’t plan to join one—nothing on them, they’re just not my scene.)

But some of those who are critical of Princeton’s privileged reputation aren’t citing statistics. Some of them, like GQ, are making lame jokes about Princeton’s supposed “douchiness.” I have no idea if I spelled that word right, but it’s an accusation that tends to put me on the defensive, because that perception is not in keeping with the Princeton I know. The Princeton I know—the Princeton I chose to attend only after I realized what it’s really like—is led by the mind-bogglingly progressive administration of Shirley Tilghman, the university’s first woman president, who has done more to take Princeton away from its 1940s and ’50s-era reputation as a Southern gentlemen’s club than anyone else in Princeton’s history. Since women were first admitted in 1969 (40 years this fall!) Princeton has been steadily changing for the better and the more progressive, and now in particular its official positions certainly cannot be said to be problematic. If there are “douchey” elements of the Princeton student culture (and there are), they are no more representative of the student body than birthers, deathers, and tenthers are of the American political spectrum. Certainly, Princeton’s douche factor is no more extreme than are those of other well-regarded private research universities like Harvard, Yale, Stanford, or the University of Chicago.

There is no reason that I should feel more embarrassed by the name of my university than my friends who go to other famous universities should. And there is no reason that I should be stopped (as I have been time and time again) after I tell someone where I go to school so that they can say to me, “You don’t seem like the Princeton type.” My own nerdy intellectual bent and investment in my coursework above all else, my passion for writing and verbal expression, my commitment to causes outside the university walls, and my investment in making Princeton a better and more progressive place are reflected in the policy decisions of the Tilghman administration and in my classmates, friends, and professors. I have to conclude that I am someone who belongs at Princeton. And by acknowledging that, I’m not implying a negative assessment of my character, either.

“Conventional wisdom” is a popular trap for this country’s discourse to slip into, particularly in the mainstream media, which perpetuate quite successfully a lot of myths that, when they don’t involve stupid things Republicans have done recently, do occasionally involve colleges with well-known names. It’s hard for me to counter these myths, when saying the name of my college and speaking from my personal experience automatically renders me an unreliable witness. People prefer narratives that criticize these institutions, so that they may be validated in their previously-held opinions that these institutions aren’t worth the hype. But I’m holding out hope that, as Princeton continues to lead its peer institutions in setting policies that make an unrivaled undergraduate education accessible to anyone who’s qualified, the university name will cease to be a source of shame, or an indication that its bearer is somehow undeserving.

High School Movies

There’s something about high school movies (and TV shows, and books) that captivates the American imagination. Even when I was in high school, I would stay up late into the night, taking out my frustration at not being allowed out after midnight by watching my illegally-downloaded copies of The Breakfast Club and Fast Times at Ridgemont High. I longed to become the Stoner or the Popular Girl or even the Goth, one of the characters who had awkward, furtive early sexual experiences or who appeared to roam a small Midwestern town unsupervised. Or, at least, I could have been one of the characters who had a car. Like so many other high school misfits, I knew where I really did fit in the stereotyped class strata: I was the Nerd, plain and simple, and I knew that, according to my favorite movies, such a status relegated me to a lifetime of loneliness and misery. The movies gave me hints for how to change, and for a time I did, trying on a few of the other labels. I watched Freaks and Geeks, and I identified ridiculously closely with the protagonist of that show, who copes with her misfitedness by joining a group of kids who don’t try especially hard in school, but who are exciting because of it, and who are silly and into music and put up with a little social awkwardness. That story, in fact, became not dissimilar from my own high school experience. And while you can’t ever shed a label like “Nerd” once you’re given it, and when it’s been yours for over a decade, I certainly tried pretty damn hard.

But when I got to college, as this blog no doubt indicates, I embraced “Nerd” for all it was worth; I embodied it and owned it. Unlike in the movies, I decided, Nerds do have productive and fulfilling lives, and it’s okay to be better at school than social relationships. It’s not a curse, at any rate, the way it is on celluloid. So now I deal with high school media a little differently: when I rented Clueless from iTunes to watch on a plane last week, or made my way through Skins on Hulu last school year, I spent every second of the movie or the episode with fingers crossed, hoping that the characters would suddenly decide not to adhere to their stereotypes: that the romantic subplot would not work out happily ever after, that the gay character or the black character would provide more than just comic relief, that the naturally pretty characters would not be made over into stylized, painted caricatures, ’80s hairdos and all.

Of course, it never does work out that way, and that’s the beauty of high school movies and part of why, I think, they’re so engrossing to those of us who have, quite definitely, moved on—physically, anyway. As I myself try to psychologically process the weird world that high school was, and to understand why things worked out the way I did, I do find myself looking to the movies and their truisms. If I had changed the way I look, I could have had a more lasting romantic relationship. If I hadn’t tried hard in school, I would have had more fun. If I had been more prone to making bad jokes, or indeed if I had conformed better to gender roles, I would have had more friends.

I obviously don’t really wish those things, and I obviously know the difference between cinema fiction and reality—where it is possible for a Nerd to lead a fulfilling life. But high school is this imaginary halcyon time, when we were all supposed to be happy, and yet—I am increasingly beginning to suspect—none of us were.We were all tortured by our own individual adolescent dramas and traumas—and whatever stereotype we ascribed to ourselves, we never embodied it as fully as characters on-screen do. We all look to them for the elusive promise of what could have been, what happiness and self-confidence we could have accorded ourselves. But high school being what it is, and the surreality of film being what it is, it will never come. We might as well get on with being who we are, and with taking solace from the knowledge that life really does get better when you have your diploma in hand.

Status Update

By the time you read this, I’ll be headed out of DC on a 36-hour journey consisting of travel on seemingly every conceivable method of transportation (bus, train, subway, airplane, car, boat…) that is, eventually, going to get me here—a fairly remote island with irregular internet and other Outside World contact. And I’m thrilled about this, because it’s my vacation, a concept I haven’t really appreciated fully before and am now very excited about.

Instead of reading the news, I’m going to read queer theory, mid-20th-century magazine journalism, and trashy novels. I’m going to hang out with my family. I’m going to sleep a lot. Maybe I’ll finally write a short fiction piece, which is one of my as-yet-unfulfilled goals for this summer.

I’m going to return to the real world on September 13, when I’ll arrive back on campus and get ready for the new school year. But until then, I will probably not be blogging or checking too much email or Facebook. I do have cell phone service, so I’ll probably post the occasional tweet from my phone, but that will be strictly one-way communication. If you desperately need to reach me, I’ll respond to emails, etc. with about a two- or three-day lag time.

See you in September!

Story of My Life

I feel like Natania Barron must have been looking over my shoulder all throughout Montessori school, mainstream private elementary school, and mainstream public elementary, middle, and high school. In her article for Wired.com, “5 Tips for Raising Your Girl Geek,” she tells it like it is for us girls who never fit in:

Geek girls don’t watch the right shows. They don’t go to the right movies. They don’t listen to the right music. And unfortunately, pop culture provides the clues by which kids sort each other out; it’s almost as obvious as the clothes they wear. When I was younger, I loved “The X-Files”, Westerns and They Might Be Giants. I quoted Monty Python and the Holy Grail with my handful of guy friends, but certainly didn’t win points in the cool crowd. Often girl geeks fall into this odd no-man’s land. We are passionate about the things we like, but share them with very few. Especially in a high school or junior high-school setting. That can lead to teasing, isolation, and ultimately, depression. […]

Many young geeklets tend to be smart. Whether it’s math, science, English or art (or all of the above), young girl geeks will excel in something. And coupled with the geeky tendencies and often bookish nature, this doesn’t exactly contribute to popularity (not that they want to be popular, but you know what I mean). […]

There wasn’t always a culture of geek girls. We didn’t always have pride, solidarity and ironic 16-bit graphic t-shirts. And even some girls don’t realize they’re geeks at all. As such, they feel like they never fit in. Even though they assert they don’t want to be the crowd, they can’t help but feel on the outskirts. This can lead to a poor self-image, which is never a good thing. While popularity isn’t important, self-worth always is.

It’s refreshing to see honest discussion about what a hard time smart, outspoken, and different girls have in school, even to an audience as sympathetic as Wired‘s undoubtedly is. However, I felt a little unsure about one paragraph. I’ve been mulling over how to talk about my complicated relationship to gender identity in this space, because I think it’s an important thing to introduce to audiences not used to thinking about gender. Weirdly enough, a problematic-seeming graf in a Wired article gives me the jumping-off point:

There are more boy geeks than girl geeks. At least, that was my experience. And many geek girls discover more friends among guys than girls. This can lead to feeling of self-consciousness and a lack of connection with other girls. While this isn’t always a bad thing, I definitely had trouble making gal friends as I got older, and assumed there were so few geek girls that it wasn’t worth the trouble. Good, enduring relationships between girls are important, not just for your daughter’s social growth, but emotionally as well. Not to mention, having tons of guy friends can be an issue when dating starts…

Oh my god, is this ever the story of my life, but perhaps in a different way than Barron intends. I remember when I was in 8th grade, and begged my mom to take me to Target so I could buy my first pair of cargo shorts. I wanted to shed my outlandish Society for Creative Anachronism-style costumes so that I could fit in better with my boy-geek friends who were having difficulty processing the fact that a girl wanted to be “one of the guys.” In many respects, that desire has driven how I’ve related to my identity as a girl and eventually as a woman for the past eight years. But I do object to Barron’s assumption of her hypothetical girl-geek’s heterosexuality—particularly when most of the girl-geeks I know, I think, identify as gay or bisexual or amorphously queer, even if they have only ever dated men. And I don’t think that’s just a reflection of my little “rainbow bubble”: they have a relationship to their sexuality that they know is non-normative, because, as Barron’s article suggests, they feel so estranged from standard and accepted models of female sexuality and appearance.

In my sophomore and junior years of high school, I went through a period of really hating womanness and femininity. I pissed off a lot of my female friends and some of my feminist male friends as well, and it’s not a period of my intellectual development that I’m proud of. When one friend told me that he didn’t see me as a feminist, it was a wake-up call, and I started to adjust how I thought about gender, and to distinguish positive femininity from negative femininity, if that makes sense. Nevertheless, I have this lingering estrangement from being a woman, and this sense that perhaps it’s not particularly important to make friends who are girls just for the sake of making friends who are girls, or that it really doesn’t matter whether you have lots of friends who are boys when you’re old enough to be dating. At least, it’s no more important than having friends who are of different races or nationalities or socioeconomic backgrounds. After all, in my experience, my male friends are more likely to date men than I am.

But (and here comes the TMI part that I do nevertheless think it’s important to have a conversation about, because maybe others can relate, and this doesn’t really get talked about ever) I don’t really date women either. I may call myself a dyke, but amorphously queer and androgynous asexuality is more my style. My social skills with regard to patterns of gendered interaction have been knocked pretty well out of balance from many of years of trying to seek acceptance from and inclusion in the boy-geeks’ club. Feeling completely alienated from the fact that I am a woman plus the complete desexualization of myself and everyone I ever interact with (necessary to get into the boy-geeks’ club, you see—to not be seen as Woman and therefore foreign/threatening) does not a healthy relationship to sexuality and gender identity make.

I am so thankful that this subject is getting some attention from Wired, and hope that maybe the boy-geeks who read the magazine will realize what a threat they pose to the self-confidence of the girl-geeks who seek entrance into their world. But I’d like to see it addressed, too, in a manner that plays to non-normative sexualities and gender identities—possibly in a way that uses queer theory to explore this relationship to femininity and woman-esque gender identity. Anyone?

So many books….

Every day, I’m aghast by how many books there are that I haven’t read, that I should read. Every time I go to a bookstore (which is relatively often at times like now, when I’m living in a city with good independent bookstores), I come out with more books that sit piled on my desk, or occasionally actually do get read. Every time I go into a library, I check out armfuls, and too often they come due before I’ve read them. I’m painfully aware of how little I’ve read, particularly the painfully obvious things that someone who wants to do what I want to do should be reading. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve smiled and nodded and pretended to know what’s going on when someone references Foucault, for example.

Sometimes I blame my post-Prop. 13 California public school for my under-read nature. I thought only this could explain my glaring gaps in classic British and American literature in comparison to my peers from east-coast schools. But maybe it’s just that I’m lazy; the internet, with its easy access to blogs, newspapers and magazines, means that I read fewer novels. I also favor the esoteric over the edifying; I’ve been meaning to read Jane Eyre for months, but every time I think I finally will go get it from the library, I get sidetracked by another memoir of gay life in the 1970s.

The British academic-humor novelist David Lodge writes about characters who play a game called “Humiliation,” wherein they try to win by naming the most embarrassing work of literature they haven’t read—one English professor wins by confessing that he’s never read Hamlet. Well, I’ve read Hamlet (and I was, if I say so myself, a very good Horatio in my 12th-grade English class’s reading), but I could think up a dozen equally embarrassing things I’ve never read. Jane Eyre, for instance, as I mentioned above. Pride and Prejudice, or indeed anything else by Austen. The Grapes of Wrath (which I faked my way through having read when it was assigned in 11th-grade English). Anything by Hemingway. I started One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, but never finished it. I’ve never read one of the more “grown-up” Dickenses—just A Christmas Carol and David Copperfield. Never read a Russian novel.

I also have to read theory, the stuff I need to talk about gender and sexuality with my friends and peers. I can’t tell you how often I’ve been told that something I wrote related to an idea advanced by Judith Butler—but I’ve never read Butler. Never read Eve Sedgwick. Never, as I mentioned above, read Foucault. Or Freud. I purport to be an American cultural history major, but I never finished Zinn’s People’s History of the United States, and as far as most other famous American historians are concerned, I can only recognize names and titles. I came to American countercultures, queer theory, and literary history through the Beats, but of Kerouac I’ve only read On the Road. Of Burroughs I’ve only read Naked Lunch. I have, however, read quite a lot of Ginsberg.

Of course, it does me little good complaining if I keep bringing home book after book that I never read. This summer, partly thanks to my daily commute on the bus, I’ve rediscovered reading for pleasure, and it’s been incredibly exciting—I can’t think of the last time I read so many books in one summer, but it must have been before high school, before I was really reading only adult books. But as I take on the task of catching up in the adult world of cultural literacy and start the background reading I’ll need to dive into my independent work at school, I’m daunted by how much there is to go. I’m sure that when I’m really an adult, I’ll still have glaring gaps in my literary consumption—everyone does; that is, after all, why “Humiliation” is such a successful joke in Lodge’s writing—but it would be nice to think that I’ll eventually catch up to the wide breadth of literature that my friends and family are able to reference.

You must be logged in to post a comment.