We would all do well to remember today one of the greatest heroes in American history.

Author: Sam

Historians and LGBT Rights

(cross-posted from my professional life at Campus Progress)

Perry v. Schwarzenegger, the federal challenge to California’s Proposition 8 led by star attorneys and former rivals Ted Olsen and David Boies, continued today with expert testimony from two historians of marriage, family, and LGBT history. Nancy Cott, a Harvard professor who specializes in the history of marriage and the family, and George Chauncey, a Yale professor who specializes in LGBT history, testified on the historical context of Prop. 8 and what American legal history has to say on the state’s involvement in marriage and in the lives of its LGBT citizens—which is quite a lot. Cott testified predominantly about how marriage is a dynamic institution which has changed over the course of American history, and which thus could change to accommodate same-sex couples as well; Chauncey’s testimony is still continuing since the court is on Pacific time, but so far he’s talked about the discrimination gays and lesbians have historically faced in America, going over some of the info he discusses in his award-winning book Gay New York, about that city in the pre-World War II period. (Full disclosure: I’m a serious Chauncey fan; I go all giggly and fluttery when his scholarship is discussed.)

As a history student, what this all demonstrates to me is the incredible relevance the study of history has to something like a court case—indeed, Chauncey first became famous for organizing the so-called “Historians Brief” in Lawrence v. Texas, the 2003 Supreme Court case which found sodomy laws unconstitutional. When a lasting American institution like marriage or, indeed, homosexuality is under discussion, the court needs historians to contextualize and interpret the present moment’s relevance to the historical narrative. You could even read the Prop. 8 proponents’ cross-examination of Prof. Cott this morning as a way of performing historiography: trying to get Cott to reinterpret what she’d said about the history of marriage to make it seem as if same-sex couples have less of a claim to that institution than her testimony had previously suggested. Of course, that didn’t happen, since the Olsen-Boies side knows what they’re doing, but it was interesting all the same.

What this further reminds me is that courtrooms are an awfully academic environment in comparison to grassroots protesting, ballot-box lobbying, and other forms of activism. For example, whereas these courtroom supporters of LGBT rights are positively relying on the expert testimony of historians, last week’s grassroots LGBT activists saw the expert testimony of historians at the annual meeting of the American Historical Association as a slap in the face of LGBT San Diegans, who have committed to a boycott of the hotel where the annual meeting took place.

Why this divide between the intellectualism of courtroom politics and the seeming anti-intellectualism of grassroots politics? (I read the San Diegan activists’ actions as a basic lack of belief in the relevance of, or perhaps misunderstanding of, what it is exactly that historians do.) I’m not sure—maybe some of you know—but I am interested to see whether the trial, which also includes testimony from a number of non-expert witnesses, will tell us.

In any case, it’s a constant reminder that LGBT rights is by no means a monolithic movement, and that each person who claims to be part of it may have radically different goals and angles for the movement.

On the AHA, the Manchester Hyatt, and Why the Modern LGBT Rights Movement Is Screwed

I read this article in my old wreck of a hometown newspaper, the San Diego Union-Tribune, and to me it represents many of the problems of mission and message facing the LGBT rights movement as it enters another decade. Excuse me briefly while I blockquote extensively:

Waving signs reading: “We All Deserve the Freedom to Marry,” more than 200 gay-rights activists and union members representing hotel employees rallied outside the Manchester Grand Hyatt on Saturday in the latest protest over the owner’s support for a ban on gay marriage.

The protesters banged on drums and waved rainbow flags while chanting “Boycott the Hyatt — Check! Out! Now!”

The rally targeted the American Historical Association, which decided to hold its annual conference this week at the Grand Hyatt despite an ongoing boycott.

About 4,000 association members — a tweedy mix of college professors, history teachers and librarians — are attending the conference that organizers decided to hold rather than pay steep cancellation penalties.

[…]

Marie McDaniel, 30, from the doctoral program in early-American history at the University of California Davis, said she regretted that moving the conference elsewhere wasn’t an option.

“I think that while many historians are in support of (the boycott), it would hurt them more than the hotel,” she said, “so they decided to do what historians can do, which is increase dialogue.”

McDaniel said she gave a presentation on intermarriage in the 18th century, showing the evolution of attitudes about such unions. For example, she said, German Lutherans used to marry only within the faith, but eventually some married Anglicans and “that was no longer seen as so awful,” she said.

[…]

Lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender groups started the boycott. Local unions have their own disputes with Manchester over labor issues at the nonunion hotel, which has 900 employees. The unions object to what they describe as excessive workloads for housekeepers; they also want to ensure job security if the hotel eventually is sold.

Commerford contended that the unions just want money, estimating that the hotel-workers union Unite Here would get $2.2 million a year in dues if the hotel were organized. He said the workers don’t want a union and noted that the housekeepers have a 4.5 percent turnover rate, much lower than the industry average.

Cleve Jones, who works with Unite Here and has been active in gay-rights advocacy, said the boycott won’t end until certain demands are met, including a public apology from Manchester and labor concessions.

“The solution is for Mr. Manchester to sit down with the community,” Jones said. “There is no one single demand to end the boycott.”

There’s a lot going on here, but I’m going to try to keep it simple.

1. It was wrong for Jones, Unite Here, and the California marriage equality groups to target the AHA. The historians have made it perfectly clear that they booked the Hyatt in 2003, which (if you’re keeping track) is quite a long time before either Prop. 8 or Manchester’s record on labor issues became clear. Had the historians cancelled the reservation, they would have had to pay $600,000 to the hotel—more money in Doug Manchester’s pockets, which is obviously the exact opposite of what’s ideal here. The AHA reportedly devoted more sessions this year to anything even tenuously related to marriage equality or LGBT rights than they have in their entire history. That’s a victory of a different kind for queer and family historians, and it’s worth noting.

2. Technically speaking, the historians were not violating any great ethical standard by going ahead with the conference. The San Diego LGBT community boycott on the Hyatt is an unofficial institution that probably very few people outside of the San Diego LGBT community know anything about; what’s more, it became official as of Pride 2008, and so the AHA booking predates the boycott. What’s more, there was no picket line to cross until the Cleve Jones camp decided to put one there. There was some shaming of historians who would choose to cross a picket line to go to interviews in the Hyatt, but that’s a highly unfair and undeserved position in which to put the historians, who have gone out of their way to rectify this situation.

3. Now, let’s think about who on which side of this conflict is doing more to further the cause of LGBT Americans. Is it the likes of Cleve Jones—who became famous again because some folks made a movie about his mentor and he was played by Emile Hirsch—who decided to protest, to be fair, a legitimately evil institution in San Diego on the day that some thousands of historians happened to be there, or is it the historians, who devoted a disproportionately large segment of their annual meeting to discussing the history of marriage, despite the fact that marriage is not the only issue facing LGBT Americans today?

Yes, Doug Manchester is evil. Yes, there are reasons not to book your San Diego vacation there. But instead of hating on the historians, maybe the San Diego LGBT groups should consider what the historians are doing to remember their movement, to contextualize their movement, to keep the knowledge of what they’ve done for the past forty or fifty years alive and to understand how an interconnecting set of factions have worked together. The historians have done the research—they’re going to be the ones telling you just how necessary it is for marriage equality to be the be-all and end-all of LGBT rights. And they’re going to be the ones telling you—as I, proto-historian, am telling you now—that Prop. 8 happened. It sucked. But it’s over, and it’s time to move on. It’s time to get over this petty tug-of-war about state-by-state marriage, and to focus on the things that will actually change people’s lives, actually make them equal in practice.

Listen, SD LGBT groups, I’m from San Diego. I volunteered for the No on 8 campaign, I went to the rallies and protests after it, I’ve stood on University Avenue in Hillcrest and watched the Pride parade go by. And I’m telling you that this is the wrong fight. Maybe you should look to the public schools in your city, where queer kids aren’t safe (and yes, I’ve been there too, and there was a reason why I know so many queer kids who dropped out or went to school across the city or across the country). Maybe you should take an interest in immigration issues, and try to keep together cross-border couples who, while they can’t get married, still would like to stay together. Maybe you should to AIDS work, or work with queer homeless people. Maybe you could even look outside of your city and outside of your country, where being gay carries a death sentence. And if I were Equality California and I were strategizing about whom to pick a fight with, the American Historical Association so wouldn’t be it.

Historians are your allies, San Diego queers! You need them—us!—to remind the kids who didn’t know that there was an LGBT rights movement before Prop. 8 that others have fought for issues besides marriage before them. Frankly, unless this movement sharply reevaluates itself, and decides to try to work on life-and-death situations instead of throwing a hissy fit at the AHA, I don’t know what hope in hell it has of achieving success in the so-called civil rights battle of our generation.

QOTD (2010-01-09)

A 1956 letter from Lionel Trilling to Allen Ginsberg, responding to the manuscript of “Howl”:

Dear Allen,

I’m afraid I have to tell you that I don’t like the poems at all. I hesitate before saying that they seem to me quite dull, for to say of a work which undertakes to be violent and shocking that it is dull is, I am aware, a well known and all too easy device. But perhaps you will believe that I am being sincere when I say they are dull. They are not like Whitman—they are all prose, all rhetoric, without any music. What I used to like in your poems, whether I thought they were good or bad, was the voice I heard in them, true and natural and interesting. There is no real voice here. As for the doctrinal element of the poems, apart from the fact that I of course reject it, it seems to me that I heard it very long ago, and that you give it to me in all its orthodoxy, with nothing new added.

Sincerely yours,

Lionel Trilling

Other fun facts to do with Trilling and Ginsberg that I discovered from the annotated edition of Howl edited by Barry Miles: Ginsberg took Trilling’s on Romantic literature and wrote a paper comparing Rimbaud and Keats; Ginsberg wrote in a letter to Richard Eberhart in 1956 that “I suffered too much under Professor Trilling, whom I love, but who is a poor mental fanatic after all and not a free soul”; in 1958 he told John Hollander that Trilling had a “tin ear” for poetry. Gasp!

I am struck by how young Ginsberg seems as he mails “Howl” manuscripts off to famous poets and professors, and then I remember that when he began to write “Howl,” he was only 28. I wonder if when I am 28 I will have already begun work on what people will consider my magnum opus, and I wonder if when I am 28 I will speak with such a naïve tone of self-assurance.

Untold Stories; or, You’re Probably Sick of Hearing Me Talk About Gay Men By Now

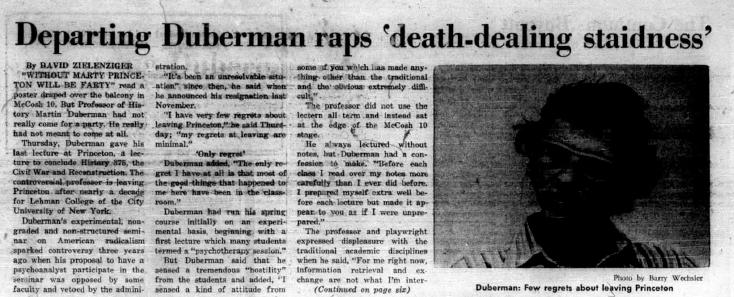

I’m doing a project for a class about Princeton and race and campus planning and things, and it’s involved a lot of archival research. This is great, because I actually really love archives—particularly when, by chance, they lead me to totally unrelated gems like this Daily Princetonian article from May 1971:

“Departing Duberman” is Martin Duberman, founder of the CUNY Graduate School Lesbian and Gay Studies Center and one of the seminal figures in queer scholarship. But you wouldn’t know that from reading the Prince article, which frames Duberman as a fairly classic child of the Sixties, whose “experimental, non-graded and non-structured seminar on American radicalism” befuddled the Princeton establishment, and whose students “had criticized him for his informality and call for spontaneity.” The article quotes Duberman, too, who appears to make no mystery of his departure to CUNY, saying, “Staidness is the best summary word for my experience at Princeton and it symbolizes what Princeton has always stood for.”

“Staidness,” however, is a pretty nonspecific word, and a glance at Duberman’s 1991 memoir Cures (the title refers to alleged cures for homosexuality) fills in some of what he might have meant when he used it. (I would like to note at this juncture that if I have any useful knowledge, knowing the queer shelves in Firestone well enough to find Duberman’s books without a call number appears to be one of them.) The prologue to Cures refers to Duberman’s time at Princeton in the ’60s, expressing his frustration at outdated attitudes to women and African-Americans, and a hostility towards radicalism or really anything different or threatening. But, gesturing towards the subsequent material in the book, this is how the prologue ends:

My private world was not nearly so comfortable [as my students’]. I lived in faculty housing—a small pseudocolonial unit built to sit “picturesquely” next to an artificial pond—and my personal life was a neat match for the antiseptic surroundings. Except for one local pub where ambivalent glances were rumored to have been exchanged by men awaiting their turn at the dart board, and the town of New Hope, about an hour’s drive from Princeton, where a gay bar was actually known to exist (though subject to police raids), the only other hope for contact was in the bushes and the men’s room at the Princeton railroad station, dim prospects in every sense. Even if Princeton had offered more opportunities, I would have been ambivalent about taking advantage of them. In these pre-Stonewall liberation years, a few brave souls had publicly declared themselves and even banded together for limited political purposes, but the vast majority of gay people were locked away in painful isolation and fear, doing everything possible not to declare themselves. Many of us cursed our fate, longing to be straight. And some of us had actively been seeking a “cure.” In my case, for a long time.

Of course, the Prince would hardly report this, because Duberman would hardly have said any of this in 1971. It’s a useful reminder of the apparent insurmountability of piecing together the history of a community that is not a community, and how much goes unmentioned when there’s not an accompanying memoir against which to fact-check.

QOTD (2010(!)-01-03)

Peter, Paul & Mary:

If you take my hand, my son/All will be well when the day is done.

I wish this were true, but it’s a nice thought, anyway.

On Larry Kramer, and Doing History

I think of myself as a pragmatist when it comes to most kinds of action and activism, more conservative than I think many people perceive me to be. And yet there is much, all the same, that I find resonates in Larry Kramer’s point of view:

Temperamentally unsuited to ceding the pulpit, he has never accepted the national gay organizations as competent advocates for gay people, and, in the wake of New York’s failure to pass a same-sex-marriage law, can only repeat his contention that state-by-state incrementalism on such matters is “a waste of time.” If it depresses him, that’s because it’s personal: “I can’t afford to wait for gay marriage in ten years!” he moans. “Unless something radically changes, I won’t be able to leave my estate in any sensible way to David, and everything we built up together suddenly won’t be there to support him. That’s criminal.”

I have been learning a lot more about ACT-UP recently, forcing myself to confront my trepidation and depression at delving into the history of the beginnings of the AIDS crisis. I more and more feel as if it is my duty to learn this history, and be able to relate it—perhaps even more so than it is my duty to learn and teach to the next generation the history of queer identities, cultures, and communities more generally speaking. As I do so, I find myself understanding why and how pragmatism is not always equal to caution. I find myself crediting radicalization with not only feeling good, but actually getting shit done—though I also find myself realizing that, as with all historical narratives, things are more complicated than it is possible to explain in any space less than that between the covers of a book, if then.

If you read that New York magazine profile I linked to above, you’ll see that Kramer is at work on a 4,000-page gay history, not just of the times since people have begun to call themselves homosexual, but of the times before that as well. For once, I do feel informed enough to say that I’m skeptical of that approach. It’s one that appears to reside in double entendres and guesswork, in superimposing the attitudes of the 20th century on earlier eras, and it’s not (I find myself presumptuously thinking) the right way to be sweepingly radical. Yes, the history of American queerfolk is still in the process of being told. Yes, we could use a definitive textbook of American queer history. But the subdiscipline is still in the process of defining itself, and the “everyone is gay” approach has nothing more to recommend itself than the “no one is gay” approach. Maybe it could be a clever commentary on historiography’s heterosexism—but maybe it’s really just bad history. In this profile, Kramer’s conviction that Abraham Lincoln was gay reads like a conspiracy theory, and an allegation difficult to make with respect to a man who died before the coinage of the word “homosexual.”

I of course do not mean to deride Kramer’s contribution to anything, and in fact I have kind of a knee-jerk reaction to the people who do. ACT-UP is evidence that we need radicalism alongside moderation to get things done, that the two work together, that factionalization can (as Amin Ghaziani says) sometimes be productive. The fact that Kramer was, apparently, left out of the recent Harvard exhibition about ACT-UP is, to the best of my knowledge, ahistorical and unfair.

But I read these stories, and I take from them lessons on how to do my own history. When you tell a history, you should not be creating it out of whole cloth—but then how to tell it without creating it, without imposing a 21st-century lens upon a cultural context you may only after years of research begin to understand as natively as you do your own?

Larry Kramer, I have the utmost respect for you, but you have given all us proto-historians (or, well, this one, anyway) an object lesson in “pitfalls to avoid when doing gay history.”

On the New Year and the New Decade; or, Continuity and Change

I have been thinking for several days about what I could possibly say to sum up this decade, or even this year, to post on the first day of a new decade. It is hard to think of something that I haven’t said before, because this blog (which I began anew in February 2009) is itself a record of the past year, its continuity, and its change. And it is close to impossible to write a retrospective of a timespan which began back in fourth grade, back before I turned ten, back when my extended family celebrated the millennium in my grandparents’ basement… back an eon ago.

This week I have been writing, for a school project, a memoir of my childhood—of my first decade, my decade of innocence. The memoir ends in 1999, the year my family moved from Georgia to California, the year (unless you’re a pedant) the millennium ended and the new millennium began. As I transitioned from childhood into adolescence into adulthood, I spent the next decade growing tired of being always angry at George Bush and Dick Cheney and Karl Rove and Donald Rumsfeld; I sought an escapist hedonistic pleasure in movies and my quizbowl team and the internet at 2am and sitting in the passenger seat as a friend drove too fast down Interstate 15. And then I sought an escape from that, in turn, exiling myself to a new world on the east coast, beginning (not without some angst) a new life in a new culture.

Then there was this year. This year, globally speaking, has been the epitome of the everlasting balance between continuity and change; we ushered it in with the inauguration of a president meant to change everything, and we came to realize that he has changed some things, but not as many things as we’d hoped he would. Those of us who were startled to political awareness by the second Bush administration began to realize just how hard it is to be a Democratic president, to advance progressive policy, to do anything but fight as hard as possible to maintain the status quo. The year 2009 in my iPhoto library is filled with pictures of marches and rallies and protests—in San Diego, in New York, in Princeton, in Washington. I have never tried so hard to bring change; I have never been so gutted when only continuity results. And at the same time, I have been growing increasingly distant, have been putting my broadening understanding of the cycles of American history to the task of understanding that this is what happens—this year, as in all other years, we fight and fight and fight, and sometimes we get what we want, and more often we don’t, yet we never stop fighting.

As I realize that my life is going to continue to be about fighting (for LGBT rights or for tenure, for peace in our time or the attention and interest of my future hypothetical students), I also realize that this year has been about becoming an adult—not just because I can drink alcohol in Canada now, which granted has been a highlight of the year. It’s because I now have just as much chance as any adult does to voice an opinion and be taken seriously; I have just as much right and just as much ability to make change. I have agency, I have independence, I have control. And, finally and most importantly (I think), I am becoming content with and thankful for what I have, perhaps because I can control my life and create for myself the conditions of happiness. I have become able to place my life in perspective, in historical as well as contemporary context, and to understand how much I have for which to be thankful.

This year has been about, in large part, the miracle of living and surviving—with the religious language utterly intended, firstly because I find it more tempting to resort to spirituality when I have thanks to give instead of altered circumstances to pray for; and secondly because there is something so beautiful and wonderful about the purest sense of human existence that it totally transcends the physicality of blood flowing through arteries and synapses firing and lungs expanding. I am not saying that I believe in a supreme being—I never have, and I don’t believe I ever will—but this year I have begun to cherish humanity, and to embrace the positive side of human continuity. We may never end our collective inclination towards making war, but we may also in turn never end our collective inclination towards making art.

And so, this year, I have put my trust in art—in paintings and photography, in music, in literature. My cultural taste has skyrocketed towards the highbrow (with, to be fair, a smattering of the pop cultural), and I’ve begun to develop my own sense of aestheticism, of beauty, of the moral necessity of seeking it. It is this conviction, this year, which has gotten me through the times when I am most ill at ease with the larger world: the National Gallery and the Smithsonian buoyed me through a summer in D.C., and the Met was there for me after the November election. High camp gets me through dirty fights about marriage equality and LGBT rights. Whistler and Mucha and Waterhouse and my friends’ art, as well, have gone up alongside the political statements on my bedroom walls. I relish the sunset; the blazing foliage of autumn and the first budding leaves of spring on the coast that’s now my home. And I don’t just survive—I flourish.

I have some New Year’s and new decade’s resolutions, of course; how could I not? Given my adult agency and the ability I must therefore have to make these resolutions true, I first resolve to keep striving to find the right balance between the personal and the political, between beauty and grit, that will make my life the most fulfilling. I need to find out how to do good without despairing, how not to feel guilty for doing things for myself, how to do both what I love and what is right. In the second place (and in the spirit of reviving conceptions of beauty long since clichéd), I resolve that I shall to mine own self be true—to be honest about what I think and what I want, and to tell the people who deserve to know the truth about these things. We are all playing roles in public, to an extent (for another clichéd Shakespeare reference, all the world’s a stage), but I will strive to make my role as faithful to my private self as possible.

A couple days ago, after enthusing to one friend about starting a book club and to another friend about starting a history society, I came into the kitchen and said to my mother, “It’s great how in college you can talk to your friends about intellectual things.” And that, dear reader, is 2009 as much as anything; in addition, it is what I hope desperately that the new year and the new decade continue to hold for me. 2009—and its education and its friendships, its ability to talk about intellectual things—is in truth, dear reader, the greatest thing that has ever happened to me. This year, for all its political anguish, has been the most fulfilling and rewarding that I can remember, and I hope dearly that I can continue to mean it when someone asks “How are you?” and I say “I’m doing well.”

Happy new year. Happy new decade. Happy every day, because there are always hope and beauty to be found.

A Response to Josh Marshall

… who wrote on Wednesday that the new body-scanning security machines that will show an outline of your body to security officers aren’t really that big a deal:

… what is pretty clear to me is the disconnect on the question that I see in the public debate.

We’re willing to ethnically profile, do all sorts extra-judicial surveillance, maintain massive databases of hundreds of thousands of people who have some vague relationship to extremism, torture captives, condemn people to hours unable to go the bathroom on planes, even launch various foreign military adventures, but when it comes to submitting to a quick scan that might show a vague outline of boobs or penises (almost certainly no more than is exposed in most bathing suits), that’s a bridge too far.

Something about that doesn’t compute to me. And what I like about this is that there’s no clear partisan division on this one. Everyone seems to agree. It just tells me that at some level we’re not really serious about this.

For the record, I’ve been against the body-scanners since there was first some discussion of them a few years ago; since then, I’ve sided with the ACLU in considering them to be inappropriately invasive. Marshall plays down the problematic side of the scanners by saying that they expose “almost certainly no more than is exposed in most bathing suits,” but seems not to consider the fact that some of us are deeply uncomfortable with the idea of wearing a bathing suit at the beach/pool in the first place, much less out of context at the airport. If I have a knee-jerk gut-twisting nausea-of-terror-inducing reaction at the idea of a stranger being able to see the outline of my breasts, I can’t imagine how, say, a Muslim woman, or a transgender person (to pick two demographics whom I figure have a stake in this) might feel.

Oh, and I’ve also been against ethnic profiling, extra-judicial surveillance, torture, illegal wars, etc. ever since I can remember, and I was 11 years old when 9/11 happened. Mr. Marshall, some of us are consistent, and some of us are still raising an eyebrow at the notion that showing a TSA agent the outlines of our naked bodies is really a necessary step in aviation security. If we can object to ethnic profiling, extra-judicial surveillance, torture, illegal wars, etc., surely it’s not too much to think that some of us might be taking body-scanning machines seriously, too?

Status Update

Well, I’m off! To the land of socialized medicine, same-sex marriage, multiculturalism, bilingualism, and a sane right wing. By the time you read this, I’ll be on one of my epic 12-hour journeys from Princeton to British Columbia, hanging out on a rural island in a house that now has a kitchen and flooring (!) for what will hopefully be the best Christmas EVAR and maybe even writing about 30 pages. Blogging will be sporadic, as will internet access—and thus procrastination will hopefully not ensue.

Best of the season to everyone. See you in the new year!

You must be logged in to post a comment.