It is just gone 6pm on an uncharacteristically beautiful summer day, and I have been distracting myself from the discombobulation of leaving by leaning out my window and watching the people hustle and bustle up and down Broad Street. There are tourists in big hats and sunglasses, and there are students in subfusc or dressed for formal halls and Schools dinners, and there is everyone in between, town and gown alike. The sun casts shadows across the storefronts and Exeter College across the road, and I have spent much of today pacing this room, thinking about how much has changed since I first leaned out this window six months ago, jetlagged and disoriented, when the sun set at 4:30 and I was newly arrived, just another American abroad.

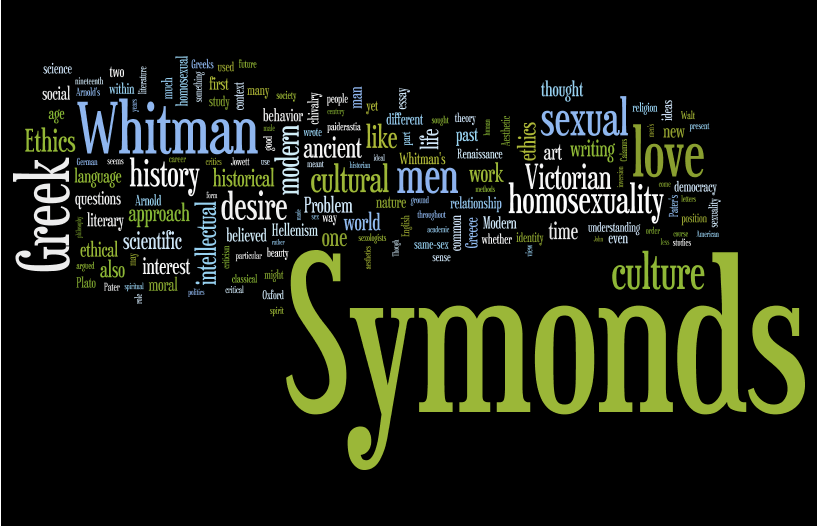

The past six months for me have been in all respects about the seductive power of this city. As the days have lengthened, I have felt its hold grow on me, even as my emotions towards it become ever more complicated. In the past six months I have wrestled with eye-to-eye confrontations with privilege and elitism, and as I have become inured to formal dinners so have I spent many hours trying to teach, pushing gently against the current of classism, sexism, and homophobia that has characterized too many of my interactions here. I have spent hours sitting in the Upper Reading Room, hours walking in the Parks or in Christ Church Meadow, hours in this room on Broad Street, hours in the Ashmolean, hours in the chapels of my own and other colleges, constantly feeling past and present collide in uncanny ways. I wrote a 45-page essay about one Oxford-educated Victorian historian who had some things to say about sexual identity, and I got to know people in this city whose secondary education and Oxford degree course mirrored his, who lived where he did and walked the routes he did and felt the things he did. And I spent hours writing essays about the latest developments in historiography; and I spent hours, particularly those of the early morning, drinking and dancing in the ways that I thought people only did in books, before I came to this city.

Oxford is a small world, a tiny enclosed space where you run into in the reading room people with whom you went to secondary school (or who know people with whom you went to secondary school) and people whom you met when you were out dancing the previous weekend. It is a tiny enclosed space in which, you have to think, those who have never left it cannot be blamed for not always remembering that there is a world outside it. For a bona fide city, some number of times the size of the Princeton campus, it can sometimes feel smaller, more insular, more suction-y. Princeton may be its own little world—the Orange Bubble—but for me Princeton has never seduced the way Oxford does. I miss my friends at Princeton, and I miss the Rocky dining hall. But I have never felt its buildings call to me. I have never felt lucky that it is a place whose streets it is my habit to walk. I have never felt it stir the promise of transhistorical connection deep within me that, before I came to Oxford, I had never felt from a place—only from books.

I finished my last Oxford academic obligation a week ago, and since then I have lounged desultorily through my daily routine, going to the library and eating in hall and spending time with my friends. I have floated disorientatedly through my life, not ready to realize that come this Sunday morning, I will have folded my life back up into two suitcases and I will be on a train away from here. I do not do change well, and I do not do leavings and losings well. I have never found it easy to leave Princeton. I am finding it harder to leave here, in a bizarre way that is new, and difficult for me to understand quite yet. When I moved across the Atlantic, I took one step closer to living a transient academic life, and the number of transatlantic connections I have made since then have reminded me that this is what academia is. Thanks to Facebook and the vagaries of academic nomadism, I know that when I say goodbye to my Oxford friends this weekend, I will do so completely confident that I will see them again. I am a historian of Anglo-American intellect and culture, and therefore there is no question that I will be back to England—and to Oxford—by necessity time and again for the next several decades. And yet. There is something about this city—just being in it, knowing it, working with and against its strange customs—that inverts your expectations of what is normal, making it so challenging to return to the real world. This is not like when you leave Princeton and mourn the loss of the embarrassment of riches that is its constant offerings of free food and t-shirts. This is something like how when you leave what Evelyn Waugh called the “city of aquatint,” the rest of the world seems drained of color by comparison.

And so rather than readjusting your sensibilities, being the better person and realizing Oxford’s flaws, knowing that this city’s life is no healthy thing to accustom oneself to, you find yourself drawn inexorably back. What I think I have learned more than anything in the last six months is why Oxford carries the power of image that drew me to it in the first place. It seduces you with the promise that you can still do good things even when you’ve placed style over substance. It is only in this city of strange ways of teaching, learning, and living that “burn[ing] always with this hard, gem-like flame” can be made truly to seem like the only way to achieve “success in life.” I have worked hard, here. But I have also every day averted my eyes from the homeless people whom this city does so little to help, have in the absence of classroom settings neglected to pay my dues at teaching others, have lived for the sake of pleasure as much as, if not more than, for the sake of bettering. All my life I have worked hard. But I have never until this term played hard as well. Oxford has wormed into my consciousness until it has given me permission to do so. And while this may be cathartic, it is not necessarily healthy.

And so when I get on a train early Sunday morning, and I leave the only place I have ever lived where on Sunday morning I wake up to church bells, I wonder if I will cease to hear the siren song that seduces me into a world of surfaces I once only knew through the written word. But somehow—and particularly as my thinking and writing about Symonds evolves over the course of this next summer, year, and academic lifetime—I suspect that I will continue to detect its echo, even a continent away. And I know in my soul, just as I know that I have fallen in love with this otherworldly place, that I will be coming back. The only question that remains is when—and what sort of person I will have become when next I set foot to pavement in the shadow of the dreaming spires.

You must be logged in to post a comment.